The Problem with the Wine Business Is Business

Constant Growth is Incompatible with Growing Wine

Happy holidays, everyone, and thanks to all of you for continuing to read my musings on wine. This one’s a long one, so buckle up. I’m also grateful today that I had been invited onto Sean Trace’s excellent podcast series Barrels and Roots (a link can be found at the bottom of this post), where we had a terrific conversation about wine’s place in the world today. I enjoyed doing the program very much, and Sean’s a great host who kept me focused – it was my first podcast after all!

And now, on with the article…

No, wine didn’t suddenly lose its place in the world. But there is still a cacophony of ponderous, handwringing, tortured voices trying to figure out what went wrong, and what to do about it. As a reader in this space, you’re already well aware. If you are #opentowork, you’re living it. I fear it will continue into 2026, and that we must hang on tight.

It didn’t become less interesting, or less cultural, or less capable of meaning something to people. What changed was the environment around it, the expectations we placed on it, and, importantly, the systems we decided it needed to live in.

Over time, as many of you and I saw firsthand, we asked wine to behave like a modern business. To conform. Which it did, quite awkwardly, and with disappointing results.

Modern business is very good at moving quickly, at smoothing edges, at creating clarity where there was once uncertainty. Wine, historically, has depended on essentially the opposite. It has always lived comfortably with delay and long arcs of time, with vagueness and variations, with the fact that two bottles from the same vineyard might not even be that similar. I’m not talking about the amazing technology that ‘sells’ wine through ecommerce platforms, nor am I talking about the high-tech platforms that ‘move’ wine from warehouse to consumer. That sort of business is required today for wineries to exist and prosper.

The modern business obsession with perpetual growth sits uneasily with wine because wine is not an extractive system. Vines have their natural limits, seasons impose delays and vagaries, and quality depends as much on restraint as ambition. Expansion, though, demands predictability, repeatability, and constant acceleration; wine depends on patience, variation, and the acceptance that some vintages and some wines simply refuse to behave. When growth becomes the primary measure of success, wine is pressured to smooth its edges, narrow its range, and favor reliability over expression. What results is not failure per se, but thinning: a gradual loss of texture, expertise, and meaning as a living agricultural product is forced to conform to expectations designed for software, or Doritos, not terroir.

For most of its existence, wine didn’t have to travel through platforms, channels, funnels, or interfaces. It traveled through people. Someone grew it, someone made it, someone carried it to market, someone bought it, and poured it, and often someone stood nearby trying, at times in vain, to explain why it mattered. Those people weren’t obstacles to modern efficiencies. ‘Markets eat marketplaces’ because optimization has no memory, valuing motion over meaning, and conflating scale with success.

As techno-business and scale entered the picture, those human intermediaries began to disappear. Not all at once, and not out of malice. They were replaced by systems that promised real market reach and consistency – a democratization of wine. Shelf tags became the communication, and scores became a clear, understandable reassurance. But this is where we start to tune out rhetorical wine-speak and replace it with capital B business. We now confuse abundance with choice.

As the market consolidated, the space for interpretation narrowed, creativity, and the artisanal faded and withered. Fewer minds and hands began deciding what reached the shelf, the screen, and the table. The business-first logic of scale favored wines that could travel easily through large systems, that could be described quickly, categorized neatly, and replenished reliably. Over time, guidance stopped coming from people with idiosyncratic tastes and long memories and started coming from filters designed to reduce uncertainty. The pandemic and the post-pandemic wine market convulsions threw gasoline on a tire fire of growth. The result wasn’t a lack of options, no, it was far worse. It was an overstocking of options that felt increasingly similar, offered without much need for thought about why one might matter more than another.

Wine certainly became easier to buy, but much harder to connect with, emotionally, thoughtfully, intellectually, or artistically.

Along with that shift came a change in language. Wine, the business of wine, began to be discussed using the vocabulary of software and growth industries. Stories are reframed as content. Relationships are now data. Loyalty is reduced to behavior. Discovery was measured by velocity. Demographics are distilled down further to psychographics. Clicks. Conversions. Retention. Subscription. None of this is wrong, exactly — but none of it captured what people actually remember when a bottle matters to them. I speak openly and often about how I react to wine on an emotional level, because it’s true, I do. I don’t mean I cry or laugh, I mean it tickles my memory. I suppose the tech-forward categorization of a consumer like me is measured by “consumer sentiment”. What I experience as an emotional response to wine would be described, in modern business language, as a ‘sentiment signal’, which tells you almost nothing about why it mattered, but it is assigned a score nonetheless.

I have been flattened out by UX researchers.

When you manage wine primarily through what can be measured quickly, you tend to favor what behaves predictably. Styles narrow. Risks dispelled. Difference becomes something to manage and flatten, rather than explore. This is why people like me, and probably you, I’d imagine, find very little (wine) to buy at the grocery store. What’s often described as wine’s decline feels to me more like a loss of texture. Erosion of people’s outright interest in wine.

Before Christmas, I went to the BevMo in Napa to see what mainstream looks like these days. I truly wanted to spend money on anything at all that looked like a good buy. I did not sweep through the spirits section (it’s not my thing), but I spent $9.99 on a bottle of Junmai sake. I only did this because I’d been in the building for more than 30 minutes and couldn’t leave empty-handed. To me, it was a beige desert landscape of banal, branded sameness. どうもありがとう、ミスター・ロボット。

Many people who say they’ve “fallen away” from wine aren’t confused by it. It’s more possible that they’re bored by it. They’re offered branding and useless information when what they really want is reassurance, all while being given increasingly false choices when what they’re missing is a human conversation. They need to talk to someone (IRL) for real. Total Wine does this with aplomb, but, of course, the wine knowledgeable help’s agenda is skewed towards certain products. But that doesn’t bother me because I know better. And it doesn’t bother the new wine customer because he doesn’t know better. That they do it (talk) is good enough.

Wine was never meant to be simple in the way mass-produced goods are simple. It carries complexity and depth because it comes from living systems, from places that refuse to repeat themselves cleanly, and from people who accept that not everything worthwhile can be summarized quickly. You can meet wine wherever you are and still belong, if you want that, but when we mistake accessibility for reduction, we do real damage. We flatten what should be discovered, we pre-chew what should be tasted, and we teach people that speed is a substitute for attention. In trying to make wine easier to sell, we quietly make it less worth staying with.

As I’ve spent more time closer to the e-commerce and fulfillment layers of the wine business, I’ve become less convinced that speed alone is the virtue it’s often made out to be. The more interesting question is whether speed actually serves the customer, or simply the system. There are models that prioritize steadiness over haste, predictability over expense, and clarity over constant motion, and they tend to create better outcomes on both sides of the transaction. The same is true in commerce platforms: the best ones don’t just move product efficiently, they make room for meaning. They stay simple without becoming generic, and they carry culture, story, and experience forward without getting in the way.

What’s interesting is that the broader culture now seems to be catching up to this tension. People are weary of systems that optimize everything and explain nothing. They’re tired of being told what they like before they’ve had time to notice it themselves. In that environment, wine’s resistance to speed starts to feel less like a flaw and more like a relief.

Wine still rewards your attention. It still benefits from being shared, as do we. It still improves when someone is willing to stand next to it and say, “Here’s why this one stuck with me.” Those moments don’t scale easily, but they’re the moments people remember, and that’s what all the business stuff is trying to accomplish anyway.

I don’t think wine needs to be rescued from business (but I do think it needs to reexamine its many unreasonable growth expectations). I think it needs better translation. More people who are willing to slow the moment down rather than rush it along. More intermediaries who see their role not as simplifying wine, but as making space for it to be encountered honestly.

Wine has endured far worse than market cycles and technology shifts. It has always survived by being carried forward through people, their conversations, and through shared enthusiasm. If it feels thinner now, it may simply be because, for a while, we replaced those conversations with systems and mistook efficiency, access, and democratization for connection.

I turned to the bottom of my wine fridge for the holidays, where all the European guys live, and pulled up some beautiful things. Over the last few days, here are some impressive wines we managed to get through:

At a pre-Christmas celebration with friends, we enjoyed a number of things, including an unphotographed magnum of Ashes and Diamonds Cabernet Sauvignon, which was dynamite. But another Napa wine made a great impression – this 2024 Inglenook “Blancaneaux” bottling of Marsanne, Roussanne, and Viognier was WAY better than I expected, and one of my new all-time favorites. Dry, highly complex, easy on the marzipan, and very lightly oaked. Hand-carried to the party by its winemaker, Jonathan Tyer, along with some impressive Oregon Pinot Noir.

The Burgundies here were mine, both showing exceptionally well, and uniquely different from each other. The Santenay (1er cru) was highly complex and developed, while the Beaune (also a 1er cru) was more rounded, powerful, and far less “four-square” than some Beaune reds. Gorgeous.

But the highlight was the 1970 Warre’s Vintage Port, which was astonishing. I handed the first glass after decanting it clean to our host Will, who commented immediately, “I thought it would be raisin-y…” And it certainly was not. It was electric, intense, lightly colored, but the brightest of clear red – no browning at all. It didn’t seem real. A better port wine, I have never had, and I’ve had some serious port wines, believe me. Age-defying, gravity-defying, sensational.

Spare a moment for this 2019 Chateau Labegorce Margaux, purchased off the shelf at Trader Joe’s for all of $34.99. It was an indulgence for me to buy a $35 bottle of anything, especially at TJ’s (where I get my Perrin Cotes-du-Rhone house wine all the time and little else in terms of wine). Where everything is getting so expensive, and Napa Cabs are north of hundred dollars routinely, this was a bottle of Cabernet that was a massive quality to price hero. I actually loved it, but why should I be surprised that I loved a Margaux? We need to look in the rearview sometimes.

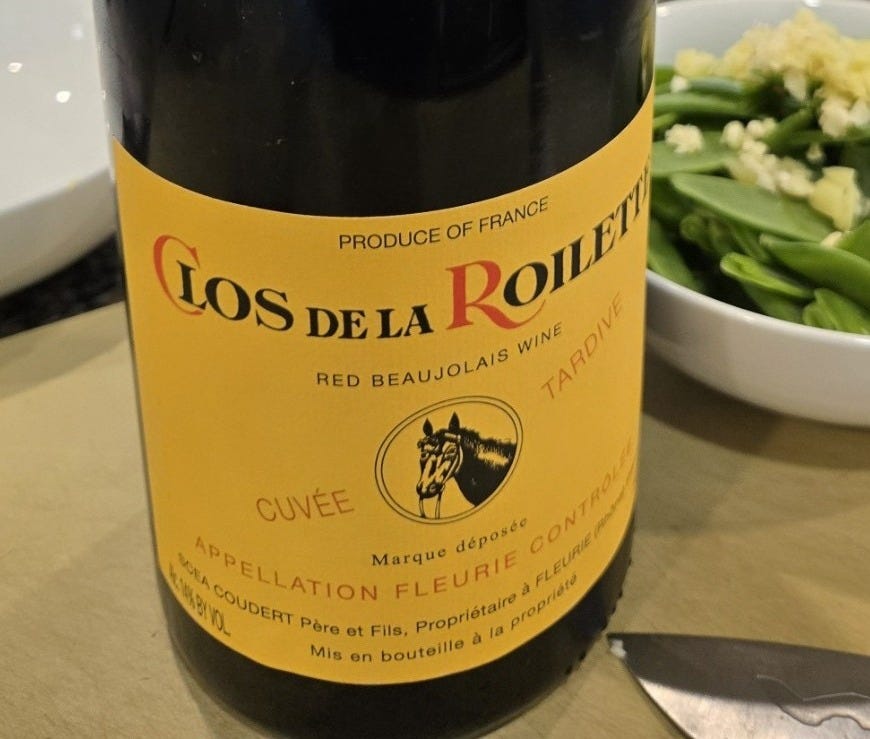

Lastly, my favorite (seriously) big-bottle-of-happiness is the 2023 Clos de la Roilette Fleurie Cuvée Tardive. There should be a law that this wine MUST be put in magnums, always. It is truly a savory, joyful experience on every level – my pull for Christmas dinner with our friends Eric and Theresa, along with Lanson Rose Champagne, and the Produttori di Barbaresco 2016, all showing great with roast rack of pork, whole roasted “gourds”, and wild mushrooms.

This sounds like awakening, watch out before you know it you will be critical of capitalism .

Edward Abby famously proclaimed “the growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of a cancer cell “

A bit long as noted, but beautifully written.